© 表現未満、webマガジン All rights reserved.

Welfare and Accidental Welfare

One thing I especially enjoy when exploring LET’S is accompanying the pick-up shuttle. The shuttle picks up and drops off clients at their homes twice a day. Back and forth it goes. It only takes twenty or thirty minutes to travel from point A to B in a straight line but driving to each client’s home and taking care of various other matters means the trip can take over an hour. It’s a great opportunity to chat with the driver.

The driver on this particular day, May 30th, was Takabayashi-san. Takabayashi-san has been working at LET’S for six years. He was originally involved in architecture and town development and used to work in Osaka and Kobe providing disaster prevention programs. He eventually realized that he wanted to get more directly involved in people’s lives and came to LET’S. Many of the staff members at LET’S, like Takabayashi-san, come from fields outside of “social welfare”.

According to Takabayashi-san, one of most interesting parts of working at LET’S is how the power of design gets called into question. Generally speaking, people without disabilities can adapt to different facilities and environments with minimal effort, even if the facility doesn’t suit them. This makes it hard to tell whether the design is actually good or if the clients are simply adapting to a bad design.

In contrast, however, LET’S clients cannot easily adjust to their environment. Things that are uncomfortable for them are uncomfortable, and they will only go places where they feel comfortable. They don’t use hard-to-use items because they are hard to use. This is easy to understand, but actually creates quite a challenge for designers.

Smiling, Takabayashi-san told me, “I think that LET’S is a worthwhile workplace for designers because it forces me to expand how I think about design and how it’s used in every aspect of the clients’ daily lives. However,” he added, “I don’t think my own approach is always right, and the most important thing is really that everyone brings different ideas to the table.”

Staff members who are architects use architecture, artists use their art, and musicians use the power of music to reach clients in different ways. Without using these tools at their disposal, they cannot handle such diverse audiences. Nobody knows who or what will be the best fit for another person, which is one reason why the staff at LET’S should also be diverse. Makes sense.

Before I came to LET’S, I assumed they must follow some kind of set instruction manual or guidelines to provide assistance, but, as LET’S representative Kubota-san explained to me, “We don’t have any manual we follow here at LET’S. Even providing assistance with eating meals or using the restroom can be a self-taught action and can be done in different ways depending on the person.”

This helped me understand a little better why LET’S activities sometimes seem so chaotic; since the clients’ needs cannot be unified nor standardized and a standardized design won’t fit everyone, the staff member’s support for them must necessarily be chaotic as well.

Anyone Can Become a “Place to Be”

Takabayashi-san told me an interesting story about Oga-chan, a young man who is a client at Takebun. Oga-chan first came to Takebun back when the center had just been established. He wanted to go out to see the shopping center, but doing so overstimulated him. The Takebun staff racked their brains trying to find ways to calm him down. Meanwhile, a man by the name of Tengyou-san, who had applied to join Takebun’s greeting staff a number of months prior, took an interest in Oga-chan.

Oga-chan was happy to go outside with him because Tengyou-san wasn’t a care worker. The staff seemed to think that Oga-chan might never return if he went outside, but he had no problem coming back to Takebun. That was amazing enough on its own, but when a staff member spoke to Tengyou-san, he explained how Oga-chan stopped by a guitar shop while they were walking and tried to buy an amplifier for twenty yen (about twenty cents in USD). Even though it’s not possible to buy an amplifier for twenty yen, he desperately wanted to and wouldn’t listen to anything to the contrary.

Tengyou-san thought that taking Oga-chan to the cash register to see for himself if he could buy the amplifier for twenty yen was the quickest way to explain things to Oga-chan. Of course, he couldn’t buy it for only twenty yen, and the clerk at the register told him so. Tengyou-san thought he might grumble a bit, but Oga-chan just let it go. The staff would have never been able to persuade Oga-chan to give up that amplifier no matter how they tried. It was the clerk, who had no prior contact with Oga-chan, that succeeded in getting him to give up.

After he finished telling me this story, Takabayashi-san concluded, “It may have been easy for the clerk to get Oga-chan to give up simply because the clerk was not a member of the care staff. The staff fuss over Oga-chan, you see. This is one reason why the involvement of people from outside LET’S is also essential.”

In this case, while unexpectedly going out with Tengyou-san, a complete stranger was able to step in totally randomly and very easily clear a hurdle that neither Oga-chan’s parents, the staff members, nor Oga-chan himself had been able to do by themselves. LET’S may very well be so open to others precisely because of these fortuitous sorts of accidents.

Takabayashi-san told me another tale of “accidental welfare”. A man named Kawa-chan also comes to Takebun. He’ll show you around when you visit LET’S and, if you’re not familiar with how things work there, you might mistake him for an employee rather than a client. Kawa-chan guided me on the first day I explored LET’S. He serves tea, communicates with other clients, and does work like any staff member.

Kawa-chan buses to Takebun by himself and can take care of eating his meals and going to the bathroom on his own without the need for any special assistance. Because of this, it seems that the staff members at the facility he used to use thought he could handle any number of different tasks and sometimes even challenged or forced him to do certain things. However, Kawa-chan actually struggled with these tasks he was given, and his inability to do some things ended up making him feel frustrated and depressed.

At LET’S, Kawa-chan has found a place where he can play an active role and he cares for Takeshi-kun, who has disabilities. When Takeshi-kun is restless, Kawa-chan will pat his head and find a way to help him. Sometimes when Takeshi-kun won’t even listen to what his own mother tells him, he’ll still listen to what Kawa-chan says.

Takabayashi-san said, “For Kawa-chan, Takeshi-kun is a place to belong.” Kawa-chan is able to perform duties like a member of the staff because Takeshi-kun is there for him. At the same time, Kawa-chan has come to represent an important “place” where Takeshi-kun can be himself.

Just like Oga-chan got along well with Tengyou-san and like how the clerk was able to calm down Oga-chan, Kawa-chan became Takeshi-kun’s “home” and Takeshi-kun became his “home”. These examples just go to show that we have no idea who will be a good match for whom, or who might be able to become “home” for someone else. Disabled or not, family or not — it doesn’t matter. This idea moves me very deeply.

Accidental Welfare

Nobody knows who might become a “home” like this for someone else, but everyone has that potential.

This idea gives me such a strong sense of hope. Even without any welfare-related skills or specialized knowledge, operating outside of the framework of “family” or “special support”, anyone can provide services for others.

Here’s what I think. Social welfare is essentially this belief that people can become an important “home” for another person. Welfare for people with disabilities lays bare a fundamental truth about human nature: aren’t each and every one of us waiting for someone like this? Someone we haven’t met yet, someone who might be delivered into our lives by chance?

We all naturally possess the potential to become a place like this for someone else. Perhaps you could say we’re each born with a “receiver” for voices that call out for just such a place to belong. We have no idea who might perform this role for another. I don’t even know what factors may make the “receiver” more sensitive — this is something that calls for deeper consideration in the future. I don’t think this concept can be explained scientifically, but each of us can become a “home” for someone else.

Put another way, the possibility of “accidental welfare” includes those of us who may consider ourselves unrelated to the present topics of discussion. Some people assume that they have nothing to do with disability welfare. There may be many people who think that welfare is an act to be performed solely by the staff members of social welfare facilities. Many people find that they don’t know how to react when they see people with disabilities in the city. I am not a professional care worker, either, and I just happened to visit one of LET’S’ facilities. Those of us not actively participating in disability welfare feel that we exist outside of it.

However, just as the clerk at the shop calmed down Oga-chan, just as Kawa-chan became Takeshi-kun’s “home”, people who are not a direct part of social welfare can still ease someone else’s burden. Everyone has the potential to become someone else’s “home” beyond the family.

We may not be recipients of disability welfare, but we do exist coexist with it and with those who provide welfare. Welfare can be accidental. And each of us has the “receiver” that we were born with. Does anyone actually live a life untouched by social welfare?

Translator : Koya sato, Anna schnell

コメント

この記事へのトラックバックはありません。

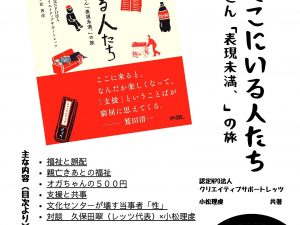

小松理虔さん「表現未満、」の旅が書籍化されました

この度、その小松理虔さんの1年にわたるレッツを観光したウェブマガジンが書籍化されました! 現代書館さんから書籍『ただ、そこにいるひとたち』として全国の書店で販売されています。ぜひお買い求めください。

この記事へのコメントはありません。